Hey there,

Here’s your fortnightly newsletter on innovations in informal transportation.

Did you miss me?

I missed me. And I missed sending out your issue two weeks ago.

Apologies.

How are temps where you are? They are crazy where I am. Dangerously crazy.

Here’s what today and the next few days will feel like according to Dark Sky.

Here it is in celsius:

That is really dangerous so I’m staying hydrated. Here’s the worst case scenario, according to National Geographic:

When people can't drink enough water, dehydration sets in. Blood flow to the skin decreases, along with the ability to sweat. Body heat builds up. A body temperature of 104 degrees indicates danger; 105 degrees is the definition of heat stroke; and a temperature of 107 degrees could result in irreversible organ damage or even death.

Hello, climate crisis.

The point

Let’s start with this point I made at MobiliseYourCity’s Global Forum at #TransportationWeek21.

“Aggregating information also aggregates power.

“What are the existing power relationships? How will they shift?

“When we make a system legible, who gets better vision?”

I was making the point that, while digitization and digital mapping can bring improvements to informal transportation, we have to be aware that aggregating information also aggregates power. We need to first study the existing relationships and power arrangements. We need to understand these relationships before we imagine our interventions or even set directions.

The panel

The panel, “'Digital solutions for paratransit integration and professionalisation,” included Fatima Arroyo-Arroyo from the World Bank SSATP program; Aman Chitakara from the World Business Council for Sustainable Development; and Antoine Chevre from Agence Française de Développement. Mateo Gomez Jattin from GIZ moderated.

The power

I used the example of the impact of Bhoomi, the World Bank funded project that digitized land records in the state of Karnataka in India in the late 90s and early 2000s.

Digitizing the land records was an anti-corruption program. According to a report commissioned by the Bank:

By and large Bhoomi has been portrayed positively by the media and has won several prizes. Independent evaluation studies have shown that Bhoomi has significantly reduced corruption and improved service delivery.

But, it had an unforeseen (or maybe not so unforeseen) side effect.

The digital land records were more readily available to people who had access to the internet and had the tools to match it with land prices across the wide geography.

Large real estate developers (mostly in the US) working for IT companies gained a better view of the market than small local developers or farmers who didn’t have access to the internet or to powerful geo-analysis. It facilitated the aggregation of properties in and around Bangalore (Karnataka’s capital) for the development of IT campuses.

One of the key findings in this 2007 report that is critical of Bhoomi, from the now-defunct Collaborative for the Advancement of Studies in Urbanism through Mixed Media (CASUMM), says:

“(Bhoomi) Subsidizes big business especially large real estate developers and IT firms. The Bhoomi program is facilitating very large land developers catering to a global IT Market. Earlier, these firms would have to compete with smaller land developers who often would provide a better price to land owners. Also, the public land acquisition process uses eminent domain via the Industrial acts (KIADB) to notify large consolidated land parcels in favor of big business that in effect disadvantages smaller firms with less capital and far less lobbying powers. Thus, what would have been illegal in previous times was from 1998 onwards, facilitated legally!“

You can read the summary of the CASUMM report (“Bhoomi: ‘E-Governance’,

Or, An Anti-Politics Machine Necessary to Globalize Bangalore?”authored by Dr. Solomon Benjamin, R Bhuvaneswari, and P. Rajan, Manjunatha) here.

I don’t really know how Bhoomi is going now or if any of these finding still hold true but the aggregation of data did create new power relationships.

I am fully supportive of using digital mapping and digital technologies to transform informal transportation, but we have to be fully aware of the possible consequences. We have to be fully aware about who gets more power and who gets less.

The plan

Which segues me to my upcoming panel this week at Digital Transportation for Africa’s Beyond Mapping: Sustainable and Inclusive Transport for Africa. (From July 1 to July 2.)

I get ten minutes on the second day. The title of my talk: “If information is infrastructure - Do you have a plan?”

I’ll be reprising some of the reasons why we worked on drafting Seattle’s Transportation Information Infrastructure Plan.

There is an emerging information ecosystem that is shaping transportation in cities. It will make getting around the city more convenient. Parts of it are run by the public sector, parts by private companies. How do we make sure it works for everyone and doesn’t discriminate against anyone? How do we make sure information serves our shared values and community goals? How do we safeguard privacy?

The virtual event is free. You’ll have to register separately to attend the July 1 webinar and the July 2 webinar. Catch me there!

The resistance

Going back to my point about the power, check out 5 Reasons Why Most Matatus In Nairobi Don’t Accept M-Pesa. It explains in very real ways the power dynamics at stake.

Have you ever entered a matatu in Nairobi or any other town in Kenya and the first thing you meet with is a poster with words such as “M-Pesa payment is not allowed,” or “Hakuna kulipa na M-pesa hapa” or “Hii gari si ya Safaricom.”

In fact, the matatu person will be very furious if you insist on wanting to pay for your bus fare using M-Pesa. Some will literally insult and call you names. Some will go to the extreme of throwing you out of their vehicle or not letting you in at all.

Here’s my summary of the reasons why matatu drivers don’t like m-pesa.

It gives the power to the customer to take back their digital fare payment and the driver can’t do anything about it. (a.k.a. “reversals”)

It takes the power away from the driver to bribe the police with cash without giving them any power to avoid police harassment.

It gives the power of knowing how much was earned to the matatu owner while keeping the matatu crew (driver and conductor) in the dark.

It gives the customer the power to make the matatu crew absorb the transaction charges

It makes the matatu crew powerless in controlling their cash flow because the bank (Safaricom) automatically uses incoming revenue to cover overdraft fees.

This wasn’t mentioned in the article but it also gives system power to the operator and leaves everyone in the dust when the system experiences an outage.

The caveat

Don’t get me wrong. We do need to digitize payments but we need to plan and design the system so we take into account the needs of all the users. We need to correct the power imbalances and don’t create new, oppressive, power dynamics.

I’ve told you all about this before.

I’ve been trying to pitch funding for a design exercise ever since, a design workshop that involves informal transportation drivers and customers.

So how might we have a design exercise on how (cashless fare collection) can improve the transportation experience and transportation systems?

How might this design exercise be human-centered but also society-centered?

How might we center cashless fare collection on the needs of:

passengers (esp. vulnerable users, minorities, seniors, disabled, women)?

transport workers?

system managers?

society and the planet?

So far, no funders have stepped up. But I will keep trying.

I’ll wrap up here.

I’ve been meaning to tell you about Argentina’s fileteado but that will have to wait, I’ve gone on way too long and I’m probably testing your patience and attention.

The persistence

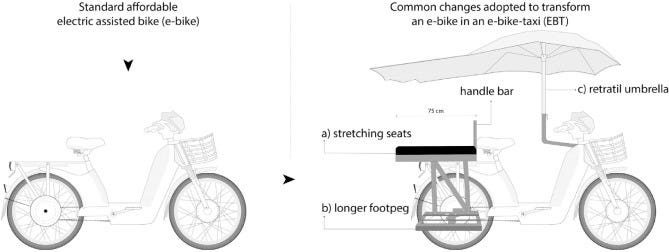

I will leave you with this paper: An informal transportation [sic] as a feeder of the rapid transit system. Spatial analysis of the e-bike taxi service in Shenzhen, China. I was particularly interested on on how informal transportation operators in Shenzen are modifying e-bikes to let them carry passengers.

They add an umbrella, a long back seat, and foot pegs. All of this is illegal but they are allowed to operate because there is no good way to get to the urban villages from the subway stations.

The informal e-bike taxicab service exists in Shenzhen in a tight relationship with the urban villages…

5.4. Characteristics of employed vehicles

No operator used a standard e-bike to carry passengers. The modifications to the e-bike allow more room for passengers and protection from weather and are relatively uniform (Fig. 1). These modifications are provided by specialized shops that are usually located in ViCs. These modifications are described as follows.

1) The extra seat is stretched to approximately 75 cm, which makes it possible to carry two passengers behind the driver or a single passenger while avoiding body contact. Single passengers often sit with two legs on the same side of the bike, a modality that is especially convenient for passengers who wear dresses or skirts.

2) An approximately 35-cm foot peg is added for passengers. It supports and provides sufficient space for two feet for either two passengers who sit one in front of the other or for one passenger who has both feet on the same side.

3) An extended 1.8 m umbrella is added. It covers the entire e-bike and protects it from weather, either sunshine or rain. The umbrella is retractable and is either hidden in a tube below the bike or closed between the legs of the driver.

You can read a man-on-the street interview with one of the drivers here (2017).

Citing safety reasons, authorities banned e-bikes from many parts of Shenzhen and Guangzhou (also Beijing, Shanghai and Xiamen). Every day, e-bike taxi drivers in areas like this one run the risk of being caught.

A driver named Wang Dana tells us that last year, police raided the places where e-bike taxis gather to wait for passengers daily. If caught, a driver could lose his vehicle. In the past, you could also get detained for riding an e-bike unless you were lucky enough to get picked up by a “good policeman.”

This year, according to Wang, the raids are less frequent. But that’s only because e-bike taxi drivers have had to contend with an even greater foe: shared bicycles.

Ok. Catch you in two weeks while I stay hydrated. Btw, I’m thirsty for comments.

I’m Benjie de la Peña and I’m the CEO of the Shared-Use Mobility Center. I co-founded Agile City Partners, and I am the Chair of the Global Partnership for Informal Transportation.

I’m convinced that informal transportation can be the single greatest lever to decarbonize the urban transport sector, but only if we stop ignoring it and instead learn to celebrate it.

The resistance is inevitable if the piece of technology doesn't favor central users.