Hey there,

Welcome back to Makeshift Mobility, your fortnightly newsletter on innovations in informal transportation.

Informal transportation is: ubiquitous in the global south; ignored in policy; despised in planning; and, represents probably the single greatest lever to de-carbonizing the transportation sector.

If your friend forwarded this email to you, please thank them for me. Why not sign up?

Did the title of this week’s newsletter intrigue you or mystify you?

If you grew up in the Philippines, you probably chuckled.

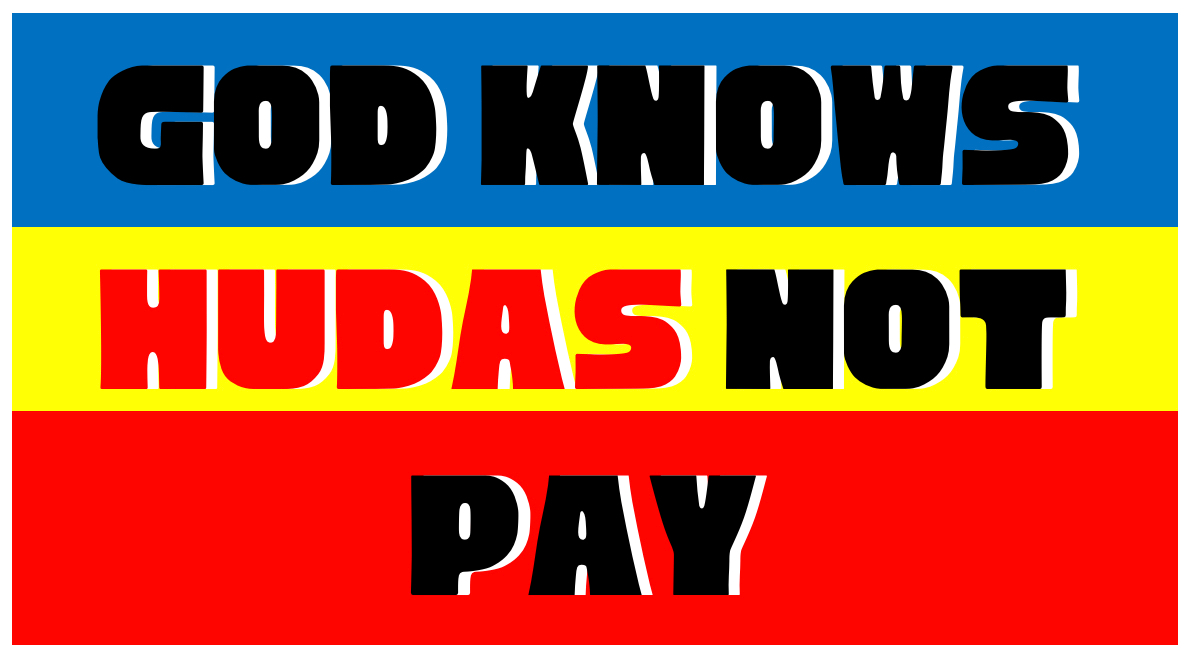

You would recognize “God knows who does not pay” from those nearly ubiquitous sign boards in jeepneys.

The signs in jeepneys were meant to shame fare evaders and would say “God knows Hudas not pay.” Whether they were effective or not, god knows.

Hudas, or Judas. Get it? Cubao Free font designed by Aaron Amar.

The sign comes courtesy of Filipinos’ naturally pun-loving culture where it is a game to say things on the sly. Probably a result of suffering 450 years of colonialism…plus 20 years of kleptocratic dictatorship…plus living with an administration that is totally bungling the pandemic response.

Slight detour: you might like this short video feature on jeepney sign painters in Metro Manila.

This form of indigenous typography is not unique to the Philippines. Apparently, sign painters in Colombia and Peru also used the same method, though not the same typeface. Proof in this wall of signs in a restaurant in Miami. Inspired by signs from Bogota and Lima.

User contributed photo from Trip Advisors

Is there a specific style of signage you’ve noticed on makeshift mobility in the places you’ve visited?

“God knows who does not pay” is also the title of an online forum on cashless fare collection (CFC) held by Move As One Coalition in the Philippines last week.

I confess. I came up with the title. It’s a joke on the joke.

The pinoy Gen Xers in the group loved it. The millennials and zoomers were “meh.”

Pun worthiness of the title aside, it is a fitting metaphor:

Governments that try to implement cashless fare collection systems on informal transit do ascribe nearly god-like powers to these electronic systems.

The promises are glowing.

This report on “Accelerators to an Inclusive Digital Payments Ecosystem” by the Better Than Cash Alliance says:

…digital payments can improve lives at the individual, community, and national levels…moving from cash to digital payments can boost productivity and economic growth, improve transparency, increase tax revenues, expand financial inclusion, and open up new economic opportunities, particularly for women and disadvantaged communities.

Nearly divine, don’t you think?

But, as always…

…the devil is in the details

Some context for the forum: the Philippines is mandating a shift to CFC as part of its public transportation modernization program. I call it “top-down, change-or-else innovation.” God-mode.

So, “God knows…” wanted to educate the public about these systems. The forum featured three commercial CFC tech vendors in pechakucha style presentations.

The vendors were generally informative BUT what was really helpful was hearing from two transportation cooperatives who also presented. The co-ops had begun using stored value tap cards for fare collection.

The co-ops said that they were generally appreciative of CFC, but there were problems.

They said this is what you would experience if you were a passenger new to the system:

The cards were not widely available. You could only get the card at the kiosks at the terminals.

No card, no ride.

You had no way of knowing how much stored value was left in your card.

You might see the value left in the card only when you tapped in to pay.

You also had to remember to tap out before disembarking or you would be charged the maximum distance fare.

Many people didn’t know how to use the cards and needed assistance.

They also couldn’t make sense of some of the error messages from the pay stations. One error for one passenger cascades into the next and the operators would then have to have the unit serviced at the end of the trip.

The co-ops wanted government to help defray some of their hardware and service costs, especially for the monthly mobile internet subscriptions.

They wanted more training and more information for the public

By far, their biggest ask was for interoperability. Their tap cards only worked for the their system. You couldn’t use it on another bus or jeep.

God knows…

…these problems are not unique.

Kenya tried CFC and failed because the cards were not interoperable. (Also because the matatu drivers liked having cash.)

“Over a million Kenyans purchased transit cards, but while many saw it as a panacea to matatus’ ills, customers, too, ran into issues. The system had in fact become less interoperable for passengers, as several competing transit cards from brands like Safaricom M-Pesa and TaptoPay were introduced to different bus lines. Until they fixed the issue a year later, passengers had to wait for certain buses that would accept their particular transit card.”

IAfrika gives a good rundown of the design failures in Kenya’s approach.

Meanwhile, Rwanda solved the interoperability problem by creating a monopoly. They went with a single CFC operator.

Despite the sweetheart deal, Rwanda’s current system still has its kinks. You can’t use the stored value tap card outside of transit. Riders still need to exchange cash for cards at the terminals.

That’s a problem with CFC. Unless the cards (or e-payments) are widely accepted, your “stored” value becomes locked-in value.

Stranded value.

This is terrible for the poor who need to be liquid.

At the crossroads

So what does work?

Roger Behrens and Herrie Schalekamp surveyed the available technologies for CFC systems in South Africa. They provide a good overview—how these systems work; what technology they use.

They looked at the “implications for passengers, paratransit owners, drivers (or on-board conductors), and regulating authorities.”

They evaluated nine systems based on:

the extent to which each system might impose an additional financial burden on the passenger

the current financial and technological means at passengers’ disposal

the ease with which a new technology might be understood and adopted by passengers, drivers and on vehicles

the major operating costs that installing and operating the new systems might impose

Their verdict? These were the best in the clutch:

The three CFC systems that achieved the best scores in the multi-criteria evaluation were all mobile phone-/mobile network-based systems: in first place was the tag-based NFC (near field communication) system, followed by the premium SMS (short message service) service and USSD (Unstructured Supplementary Service Data) system which are both in widespread general use.

These were the laggards:

…of the three worst scoring systems, two relied on the passenger having a bank account (QR-code, credit card payment) and one on creating a free-standing fare management and payment system (closed NFC card system).

Caveat that this study is from 2017.

Fare collection apps from ride hail were still scaling up and were yet to jump from just being a way to hail and pay for transport to being payment systems meant to rival credit card networks.

Because the payment apps players have their eye on the larger market, the interoperability problem will probably solve itself.

These super-apps aren’t content with just transit payments. They want you to use their app for groceries, for your salon visits, in restaurants, in convenience stores. They want you to use it to pay your utilities, your rent, even your mortgage.

The growth potentials are huge.

Here’s the space in two LatAm economies alone: 85 percent of Brazil’s market still relies on cash; in Mexico, it is 90 percent.

There’s the market and then there are national government policies creating more space.

Aadhaar, India’s national digital ID system is also designed to be a platform for digital finance. They want to build a National Common Mobility Card (NCMC) initiative that calls “for ‘one nation, one card’ to create a seamless travel experience across all public transit modes.”

One card to rule them all. One card to bind them.

Ambitious. Worrying.

Specially because aadhaar has serious privacy issues.

India’s inefficient, unsecured centralized data system offers a cautionary tale for the rest of the world. Electronic records for citizens can, in theory, improve public services and reduce administrative costs. But centralized electronic records do so at the cost of its citizens’ basic rights.

Losing your basic rights.

Maybe also losing power.

…who has the power

Creating these digital systems changes the power relationships.

Unfortunately, they tend to centralize and aggregate power.

Going back to Behrens and Schalekamp:

Perhaps the most crucial consideration is that the introduction of CFC would fundamentally impact on the relationship between paratransit drivers and vehicle owners. This applies irrespective of which technology might be used…

Removing cash from the vehicle means that the role of the driver in the fare transaction is diminished, if not entirely negated…Drivers would lose the flexibility to determine their level of effort and income. These are not inconsequential changes, and would require concerted engagement between owners and drivers.

Power isn’t just about control (benign or malevolent), it’s also about trust, something the informal economy is apparently very good at.

Makes sense. Informal systems rely on person to person contact, person to person trust. Digital systems require trust in a faceless algorithm. It’s all in the design.

So, who needs a design spec for trust in CFC?

The emerging landscape may solve the interoperability problem but how might we have a system where the digital cash also improves the performance of the transportation system? How might we have CFC systems that build societal trust and solidarity?

Those how might questions can only mean one thing: a design exercise!

So how might we have a design exercise on how CFC can improve the transportation experience and transportation systems?

How might this design exercise be human-centered but also society-centered?

How might we center cashless fare collection on the needs of:

passengers (esp. vulnerable users, minorities, seniors, disabled, women)?

transport workers?

system managers?

society and the planet?

How might I put together a virtual design exercise? (And who should be at the table or zoom meeting?)

How might I get you to participate?

How might I get you to leave a comment?

Seriously, if there’s one thing you take away from this issue, please read the Society Centered Design manifesto. Society needs it. We need it. Every design exercise needs it.

Last tidbit before I let you go:

Implementing cashless fare collection is a challenge even in formal transportation systems in rich economies.

This guy pays with his phone.

Ok. Catch you in two weeks.

Remember, God knows who wanted to leave a comment but didn’t. (Ha!)

Stay safe. Wear a mask.

I’m Benjie de la Peña, a transport geek and urban nerd. I live in Seattle which was a transit success story but now the mayor wants to cut transit funding.

I think a lot about strategic design, institutional shifts, and innovation.

I believe makeshift mobility could be the single greatest lever to de-carbonize the urban transport sector -but only if we can organize. If I had my druthers, the world would have a international, inter-city think tank dedicated to improving informal transportation.