Hi there,

Here’s your fortnightly dose of Makeshift Mobility, your newsletter on innovations in informal transportation.

I’m in the Pacific Northwest where spring has sprung and the long days of sunshine are starting. That makes it very hard to stay indoors and work on newsletters and the like.

Still, I’m happy for the sunshine, even if it mostly comes through the windows.

How’s the weather where you are?

The wisteria on our gate hasn’t bloomed yet, but this is what it looks like when it does. I can’t wait.

Makeshift mobility (still) matters in a post-COVID world

Let’s start with this great post on WRI’s TheCityFix from John Surico.

John discusses the importance of informal transportation in post-pandemic recovery plans, sharing the findings from research by PEAK Urban.

He first looks at research by Jacob Doherty in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire who frames the role of informal transportation in “filling in the gaps.”

Mostly the gaps ignored by formal transportation. Gaps that are gendered and exclusionary.

“Crises seem to always provoke expansion and development for informal sectors,” says Jacob Doherty, a PEAK researcher who focused his research there.

In Abidjan, that takes shape in three general forms, says Doherty. There are gbaka, or mini-buses that run on longer, fixed routes; a “pool”-like communal taxi service whose destinations are generally determined by the next passenger in line; and salonis, an emerging taxi-tricycle…

For his field work, Doherty spent time with mothers who relied on these modes to get their kids to school. The women, he said, rarely go into the city center, and instead conduct short peripheral trips — commutes often overlooked in transport planning, which tends to emphasize economics. “One planner explicitly said, “Don’t they [mothers] just stay at home? You should be looking at how people get to and from work,’” Doherty told me.

In that sense, he argued that mothers in Abidjan already live in the much-lauded “15-minute city,” an increasingly popular trend that envisions residents being able to conduct all essential activities within a short walk or cycle. But the major infrastructure projects going in — new bus rapid transit, new metro lines — are still focused around the downtown, he said.

John then takes us to Beijing.

Informal transport plays another key role — it helps get people out of cars.

PEAK researchers in Beijing found that urban fringe residents are often subject to the phenomenon of “forced car ownership,” where they must bear the economic costs of an automobile due to limited access to jobs and services, like public transit. “Travel time and cost in the urban fringe areas are significantly higher than both the urban and rural areas,” they said. Residents are living in — yet disconnected — from their own city.

But informal transport can be there fast. And when shifts happen, like we’ve seen in the last year, they can sometimes be more responsive than built systems.

I would say not sometimes, but always. Informal transportation is ALWAYS more responsive than built systems.

John wraps up with an argument that I very much agree with: informal transportation is resilient and innovative.

Using a model based on time and convenience, they concluded that boosting efficiency could be a path forward for public transit. Ease every barrier, from contactless payment to reliable service, and avoid chokeholds. The pandemic was an exercise in the opposite, as limited capacity meant less frequent service, slowing down trips and making the car appealing. “Add in face masks, temperature checks, hand sanitizers,” he said. “Those times add up to a very large chunk that we’re paying as commuting time.”

Informal transport, he argues, can help. Perhaps it’s a mototaxi to a bus, with payment platforms and schedules that match up. Or special lanes for shared taxis to breeze past single-use vehicles. Anything that helps make the experience more seamless. “I do think that will attract people right now,” Prieto Curiel argued.

Transit has to be more equitable, inclusive and sustainable — a global pandemic shouldn’t have to tell us that. Once again, informal operators demonstrated their immense value in meeting these goals, although too often at a detriment to themselves. Cities should not make that mistake again: including informal transport in recovery plans could make life better for all the key players that make up our urban landscapes — riders, operators, agencies, and the places they call home.

It’s now up to cities to decide what comes next.

We need to embrace informal transportation to make our cities more equitable. We need it because the people who create makeshift mobility, and the people who use makeshift mobility cannot wait for the slow gears of planning and building formal transportation.

People, platforms, mobility

This lead came through Giulio Quaggiotto. (Thanks for tagging me!)

Digital Hub Asia has an excellent interview with Rida Qadri on the the mobility and gig economy in Indonesia. Rida is a PhD Candidate in Urban Information Systems at MIT. She wrote that great piece in Slate on Delivery Platform Algorithms Don’t Work Without Drivers’ Deep Local Knowledge. (I shared that with you a while back.)

Digital Hub Asia prefaces their interview:

Indonesia is the largest market in Southeast Asia and one of the most dynamic digital economies in the Asia-Pacific region.

The Ojo (motorbike taxi) is considered to be a cultural symbol and key mobility artery to many Indonesians. Today, platforms Go Jek and Grab, global Decacorns (sic) each valued over 10 US$ billion, have built an entire platform economy with a suite of on-demand mobility, delivery, e-commerce, and payment services around the Ojo. [Note: I think that should say “ojek.”] While these platforms change urban life in Jakarta they are also being changed by it. In Indonesia, local context and urban culture challenge western narratives and best practises of how platforms function and design their services. Case studies and observations from Jakarta are extremely relevant toward understanding the mobility platform economy today and how it may evolve in the future. In Indonesia and around the world. (Sic.)

The great thing about the interview is that Digital Hub Asia broke it down into short segments of five minutes or less.

My favorites are Rida talking about “offline matching.” Basically it mimics the old practice of going to a pangkalan—an ojek station—to look for a ride vs. opening an app to hail one. The tech just facilitates payment

Rida refers to pangkalans as “spatially rooted stations.” They seem to me, very much like Kampala’s stages, or the wins of Bangkok’s sois.

Rida thinks offline matching “started because Grab realized the inefficiencies of (online) algorithmic matching.”

Jakarta has terrible traffic and there are many “places where it would be faster for you to street hail a driver as opposed to waiting for the algorithm to match you.” Or faster to walk to a nearby pangkalan and get a ride there.

Rida continues:

When the platforms came in, they assumed that these spatially rooted stations would disappear because there is no need for them. There’s no need for them. You don’t need to be located in a group in a particular area. But actually they didn’t (disappear). Drivers continued to hang out in groups. They continued to form these clusters. They even started to develop their own, what they called “base camps”-these DIY shelters across the city.

The other reason for the offline matching, Rida tells us, is that there were so many ojek drivers in Jakarta that it would cause so much congestion to have them circling around or waiting in queues.

It was also interesting to learn that not all ojek drivers use ride hail apps and there are spatial politics of where online ojeks can pick up passengers if there is a nearby pangkalan.

Rida also talks about how local knowledge is so important to ojek drivers, not having it would completely hobble operations. (Like knowing where to park closest to a restaurant for food pickup at a mall, or having “mall experts” who can pick up the delivery from a store in a mall and hand it over to the ojek.)

Grab and Go Jek are trying to figure out how to capture and integrate that knowledge into the app. Rida isn’t so sure it will work and questions whether that will further devalue the labor and contextual knowledge.

Digital Hub Asia serves Rida’s deep knowledge in nine easy chapters:

Offline matching: A case study on how local context shapes global platforms

The Emerging regulatory landscape for mobility and delivery apps in Indonesia

You can go through them sequentially or choose and pick.

Makeshift mobility always gets the stingy end

Here’s a quick take from the recently released report on land based transportation from the Competition Commission of South Africa.

They looked at allocation of government investments in transportation in the country.

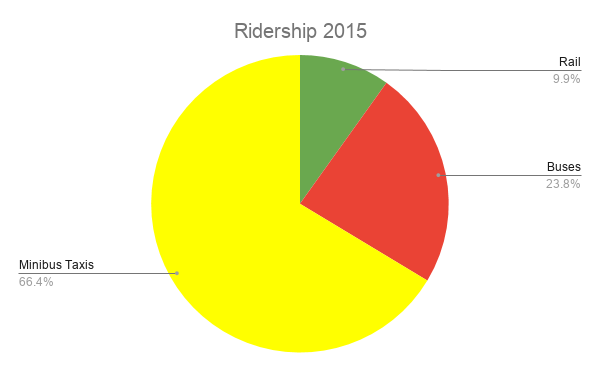

Rail gets 57% of the investment, buses get 42%, while minibus taxis get a measly 1%. (Basically, investing in new vehicles via SA’s taxi recapitalization program.)

They put that up against ridership.

Of the people who used public transportation, less than 10% used rail. Less than a quarter used buses. More than 66% used minibuses.

Budgets, they say, are moral documents. I think they also represent the “urban mobility imaginary” of the economic and political elite who think only rails and sleek buses are valid investments for transit.

Quo Erat Demonstratum.

“Dollar Vans, Jeepneys, Matatus, Oh My!”

I leave you with this episode of CoMotion’s Fast Forward that I got to co-host with NewCities’ Greg Lindsay.

We talk about informal transportation and Greg interviews Su Sanni. Su founded Dollaride, a startup focused NYC’s home grown makeshift mobility: dollar vans.

That’s it for this week! Leave a comment and share if you care.

I’m Benjie de la Peña and I’m the CEO of the Shared-Use Mobility Center. I co-founded Agile City Partners, and I am the Chair of the Global Partnership for Informal Transportation.

I think we need to challenge the existing urban mobility imaginary, that is still driven by modernist notions of control and efficiency.

I’m convinced that informal transportation can be the single greatest lever to decarbonize the urban transport sector, but only if we stop ignoring it and instead learn to celebrate it so we can transform it.