Ciao bella!

Welcome back to Makeshift Mobility, your fortnightly newsletter on innovations in informal transportation.

How have the first few weeks of 2021 been treating you? Did you breathe a sigh of relief when you welcomed the new US administration? Is it good to know that fighting climate change is back and central to the US federal government’s agenda?

I did.

I hope this brings new effort to decarbonizing the transportation sector in the US and around the world. If you’re involved with organizations that focus on that work, I have three words for you: decarbonize informal transportation.

Ok. I’m stepping off the soap box. I’ll talk less and share more with this letter. But, I warn you, this issue is quote heavy. I hope you don’t mind. These are just such interesting articles that I can’t help but share them with you.

Here we go.

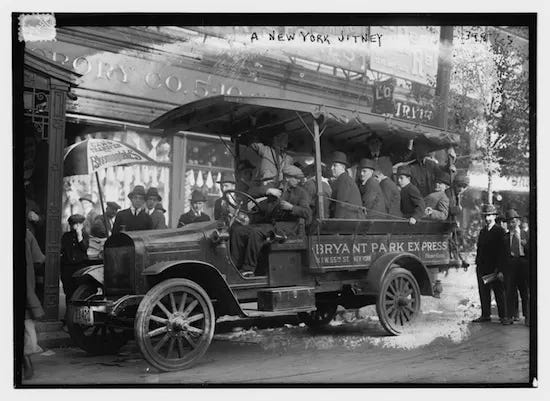

Jitneys and political power in the US

First, you should read this absolutely amazing article from Pacific Standard Magazine (PSMag) from nearly a decade ago.

In 2012, Matt Novak offered not so optimistic advice to Uber on how to deal with cities and regulation based on the experience of the jitney from a century ago.

Matt’s advice didn’t exactly age well. He said, “It remains to be seen how long services like Uber will continue to exist as long as they continue to disrupt the established taxi industries. But if history is any guide, you can't fight City Hall. In the meantime, anyone for slugging?”

Matt’s prognostications aside, I’m sure you know that what got me excited is the accounting of the history of the jitney and the early start (and eventual demise) of informal transportation in Los Angeles and the U.S.

Matt writes:

The 1910s saw the rise of the automobile, and along with it, the rise of the ride-sharing and alternative taxi service. Many of them unlicensed, they were known as a "jitney," costing just a nickel, or about $1.10 adjusted for inflation. (At the time, the word "jitney" was slang for a nickel.)

(TIL: Jitney was slang for a nickel. Matatu is short for mapeni matatu or thirty cents.)

Matt continues:

The first known jitney in the U.S. started in Los Angeles in 1914. Thanks to the mild climate of Southern California, which allowed for the rapid expansion of open-air automobiles in general, there were an estimated 700 jitney vehicles on Los Angeles streets within a year. As Scott L. Bottles notes in his book Los Angeles and the Automobile, "By late 1914, some enterprising motorists had established the nation's first jitney companies, using oversized automobiles to ply the streets in search of customers. The automobile jitney offered flexibility, convenience, and speed to those disappointed with streetcars."

Jitneys were seen as direct competition for the nation's streetcar services, many of which were angering riders over their unwillingness to improve their overcrowded and increasingly undependable services at a time of recession. By 1915 the jitney vehicles were carrying about 150,000 Angelenos per day and the jitney had swept the nation, operating in more than 40 U.S. cities including San Francisco, Seattle, Denver, New York, and Portland, Maine

I wonder what the famously car-obsessed metropolis would look like now if the authorities just let jitneys be and found a way to integrate them into the streetcar system. Maybe the whole integrated system would have thrived, maybe even avoided the tragic demise of the LA streetcar network.

My other take-away is how the original intent of the system shapes the paradigm. Jitneys, matatus, jeepneys emerge from real ride-sharing, e.g. having more than one (or two) persons take advantage of a vehicle and a route thereby maximizing utility.

Uber and the other TNCs that deliver what is more accurately termed “ride-hail” not ride-share, emerged from “having a personal black car driver.”

Not about sharing and the collective, but about personal utility.

That piece led me to a longer piece from Pilcro on the history of jitneys in North America (more specifically in Vancouver). Pilcro discusses the politics:

While riders were enthusiastic (about jitneys), local governments were not. Jitneys diverted riders from trams and streetcars, breaking monopolies on transportation and ultimately taking money from cities’ pockets. City councils took measures to curb the use of jitneys. They imposed taxes on operators, while commentators at the time raised concerns about safety and public morality (they reckoned that young couples would use the curtained-off back seats to neck).

Kansas took an interested tack. They hired a Jitney inspector. The inspector’s first order of business was to guarantee the safety of the vehicles, and to make sure drivers had correct insurance; this latter issue still comes up in discussions around ride-sharing today. Although these measures improved public confidence in jitney services, the added cost of paying for insurance as well as bringing their vehicles up to spec was too much for many operators to bear.

By the time the 1920s hit, jitneys were about done for. Restrictions enforced by cities - such as banning the cars from the same streets were trams operated - and rising taxes forced most drivers out of business. The cities, and the companies in charge of mass transit, had won. Jitneys were in constant competition with one another, as well as with the city; they didn’t present a unified front. They didn’t have the funds or unified organization necessary to lobby the government or sway public opinion.

Let me repeat that last line:

They didn’t have the funds or unified organization necessary to lobby the government or sway public opinion.

Meanwhile, the technology-enabled, venture-funded, shared-use companies of today certainly have the money to lobby government and sway public opinion.

At the Global Partnership for Informal Transportation, we’re thinking about how to leverage the technology companies to transform informal transportation; to move people out of precarity and improve the whole system for the people, for the community, and for the planet.

We can’t do that without understanding local power and local knowledge.

Cue to jump both time and space to today.

Here’s two pieces for you on ojeks in Indonesia and xe ôms in Vietnam, two-wheelers grappling with the entry of technology.

The first is about the power of local knowledge (and how you cannot capture that in an algorithm). The second is about the power of local relationships.

(Hat tip to Giulio Quaggiotto who tweeted about these pieces first. If you’re into innovation, you have to follow @gquaggiotto.)

Ojeks and the power of local knowledge

Rida Qadri brings us this story of how the Gojek and Grab drivers in Jakarta actually rely on their own back channels to share local knowledge–critical information not served up by the algorithms of the billion-dollar, decacorn companies.

Rida writes:

Much has been written about the frictionless technology of ride-hail platforms celebrated by customers and technologists alike. Startups like Gojek and Grab have become decacorns (companies with valuations of $10 billion or more) on the basis of finally providing a simple technological solution to the chaotic mobility markets of the developing world. Yet their elegance is powered by and relies on the human mediations of the drivers on the street. It is the local markets they claim to replace that have often furnished drivers with the knowledge of local physical and social constraints.

In Jakarta, the seamlessness of the operation of both digitized and nondigitized bike taxi markets depends on particularities of street network morphologies, traffic conditions, and spatial clustering of bike taxis on streets. It is the task of the driver to bring together the two visions of urban space: the abstract and the grounded. Yet the celebration of digitization renders the driver completely invisible—even though it is their knowledge and ingenuities that allow the technologies to appear frictionless. Even as algorithms become more complex, that local, granular knowledge is difficult to replicate. There will always be unknown optimizations algorithms will miss and real-time hurdles that tech firms, no matter how organized, will remain unaware of.

Xe ôms in and the power of local relationships in Vietnam

Ashley Lampard brings us this story about the resilience of xe ôm drivers in Hanoi against the onslaught of technology.

Ashley writes:

There are around 10,000 xe ôm drivers still working in Hanoi. Most are male, in their 50s, and have little formal education. Few regularly use smartphones. “They hurt my eyes,” Nguyen says. “My eyes are old women’s eyes!”

But even in rapidly digitizing Vietnam, which has emerged as the most recent battleground for Southeast Asia’s ride-hailing and food-delivery giants Grab and Gojek, the xe ôm drivers are proving unusually resilient. The almost familial relationships that xe ôm drivers have built within their communities are practically impossible to replicate through a one-size-fits-all technology platform, demonstrating the difficulties that venture-backed unicorns face as they try to build regional businesses.

…But while ride-hailing companies might be able to make the case to regulators that they are breathing life into a moribund sector in need of modernization, they may find cultural barriers harder to overcome. Many consumers in Vietnam prize the personal relationships they have built with their xe ôm drivers and are unlikely to sacrifice those for anonymous reviews on smartphone screens and impersonal conversations with customer service centers.

What do you think? Did you enjoy those pieces? I hope you did.

I leave you with three more short links.

Robert Neurwirth writes in City Monitor about the electrification of small vehicles (including the auto rickshaw). Robert wrote Shadow Cities, one of the books which influenced me to start work in informality in cities.

Deccan Herald features the work of Three Wheels United to help auto rickshaw drivers and operators go electric.

Cities Today tells us that WhereIsMyTransport has completed the digital mapping of the transportation system in Bangkok (formal and informal).

And, if you haven’t, do register for Transportation Inflection Reflection, my one hour discussion with Dr. Adonia Lugo, Alissa Walker, Stefanie Brodie, and Alissa Walker. We’re talking deep systems change.

That’s on Wednesday, February 17, 2021 (1130AM ET/1030AM CT/ 830AM PT).

That’s it for this edition. Meet you back here at your inbox in two weeks. Meanwhile, leave me a comment.

Ciao!

I’m Benjie de la Peña and I’m the new CEO of the Shared-Use Mobility Center. I co-founded Agile City Partners, and I am the Chair of the Global Partnership for Informal Transportation. My cats are not impressed.

I got myself a tandem electric bike to celebrate the new year. My cats are not impressed by that, either.

I trying to convince my cats that makeshift mobility could be the single greatest lever to decarbonize the urban transport sector, but only if we stop ignoring it and instead learn to celebrate it so we can transform it.

“Meow.”

I'm fascinated about the story of jitneys in Los Angeles because this is the first time I've read about it. One always hears about street cars and the Red Car, but barely any mention of jitneys. :) Thank you for the ride back into history!