Hey friend,

It’s been a moment. I hope you’ve been kind to yourself.

Here’s your dose of Makeshift Mobility, a fortnightly newsletter on innovations in informal transportation.

In my last letter, I took you on a short tour of marshrutkas.

It was a discovery for me as I didn’t know how extensive the geography is served by the slavic route taxi. (From East Europe, to the Urals to the ‘stans.)

I have this fantasy of a tv documentary series, ala Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations, but instead of food we’d take rides on the different kinds of informal transportation across the world. Don’t you think that would be awesome? (If you know someone from Netflix, or Amazon, maybe you and I can pitch it.)

Of course, the late chef did include rides in popular transportation in many of his journeys. Can’t really get the local flavor riding around in an uber.

If you were as fascinated as I was of marshrutkas, you can dive even deeper via this twitter thread from Gaurav Mittal. He shares links with research that looks at the impact of ride hailing services; the connections between the working conditions of informal transport workers and mobility conditions; and, (my personal favorite) the “semiotics of decorations” on marshrutkas.

Fair warning that most of the articles are behind paywalls.

Pro-tip, you can contact the author directly and they are usually happy to share a copy of their research. And, no, they don’t get any of the money you pay to access their research.

ICYMI, I told you about Gaurav’s own work in letter #19.

I am excited about connecting this emerging global network of researchers and that’s part of the work I hope we can do through the Global Partnership for Informal Transportation.

If it was the jitney ditties that caught your attention from my last missive, here’s a great post from Don Anderson on lyrics and recordings of these American jitney ditties.

This week, I’m diving into the angkot of Indonesia.

Follow along and maybe we’ll learn a phrase or two of Bahasa.

Namamu siapa?

(What’s your name?)

Angkot are four-wheeled informal transport vehicles that serve the cities and towns of Indonesia. Usually, they are small minivans in that can carry about 11 people; a dozen in a pinch. But, there are intra-city angkot that are mini-buses and carry 20-30 passengers.

"Angkots" or --- short from “angkutan kota”, which means ‘city/town transportation’. It’s called “pete-pete” (read: pay-tay pay-tay) in Makassar, “bemo” in Kupang, “mikrolet” for some routes in Jakarta, and “taksi” (which literally means ‘taxi’) in some places in Sumatera.

You enter an angkot via the side door on the left.

Beside the driver’s seat there’s a spot for one or two passengers, just like in any regular cars. But the seating arrangement for the rest of passengers in the back is usually turned sideways, that is 2 rows of seats (and by seats I mean a long bar with minimum upholstery) facing each other. In some cities, like Manado and Balikpapan, the seats are all facing front.

Apa warna favorit Anda?

(What’s your favorite color?)

Angkot come in solid colors, sometimes with some broad stripes of some contrasting color. From what I can tell, the color schemes don’t indicate route but may indicate city preferences, with some agencies mandating a particular livery.

Local governments tend to crack down on more flamboyant (read: “overly decorated”) angkot. Of course makeshift mobility is so much more than transportation, it involves culture and self-expression.

Cantik sekali

(So pretty)

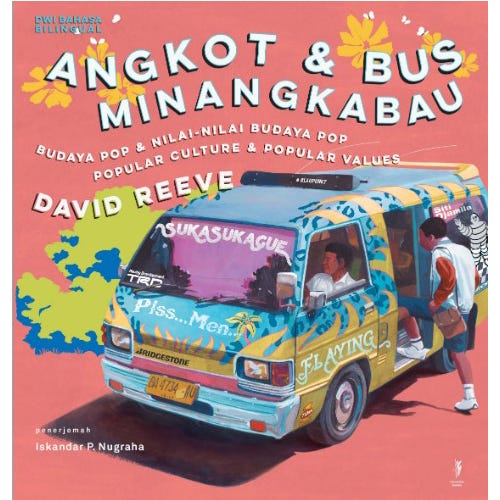

David Reeve, with Iskandar P. Nugraha, wrote and illustrated a lovely book on the decorations of angkot in the city of Padang, West Sumatra.

David tells us about the project in an interview with the Australia Indonesia Youth Association.

[Q:] David, what is Angkot dan Bus Minangkabau all about?

[David:] Witty words and phrases, bright colours, pictures and symbols – these are the elements in a tradition of decoration of various kinds of transport in different parts of Indonesia: becaks, bajajs, trucks, bemos, buses and passenger vans (angkot) … sometimes combined with booming music. The trucks of the north coast of Java are famous for sexy or pious pictures plus snappy phrases. Buses north and south of Yogyakarta are often covered with big pictures and a range of phrases and slogans. The angkot of Medan and Makassar are sometimes quite boldly decorated. But the peak of all this decoration is found in West Sumatra, particularly on the fabulously decorated angkot of the city of Padang, and in a range of buses, large and small, including Padang city buses (now disappearing), and intercity and interprovincial buses. The book Angkot dan Bus Minangkabau is an attempt to record, celebrate and analyse this dramatic and fascinating phenomenon of popular art, popular culture and popular values.

…I was really only intending to make a collection of teaching materials, but as the word bank and picture collection grew, I began to see that there were very specific themes recurring in the data … and that these themes represented various values, and further that the values endorsed there were very different from the ‘standard’ or ‘official’ version of Minangkabau1 values. I came to see the popular culture expressed on the angkot and buses as showing a counter-culture, in opposition to official values. So I started with a language collection but ended, almost despite myself, writing something more like sociology and ethnography – based on a corpus of language items.

Berapa banyak yang kamu punya?

(How many do you have?)

I couldn’t find any national counts for angkot (and all its iterations), which is par, of course, for informal transportation. There are counts at the metropolitan level.

In Jabodetabek—what the locals call the Greater Jakarta Metropolitan Area—there were about 47,000 angkot as of 2015. Rémi Desmoulière writing for The Conversation, shares the numbers and tells us about the resilience of angkot.

Their existence in Jakarta is not simply a matter of meeting the needs of public transportation. Their prolonged existence relates to their social and political functions and the interests of thousands of employers and workers in Jakarta.

The number of minibuses skyrocketed in Jakarta first before they spread to surrounding areas. For Jakarta alone, the number of angkot increased from 5,000 units in 1968 to 13,500 in 2015.

For both angkot and medium-sized buses, the latest data from 2015 show that there are 47,000 operating units in the Greater Jakarta Area (this includes Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang and Bekasi).

Inovasi

(Innovation)

I often get asked some version of the question, “What cities have successfully transformed informal transportation?”

I reply, “Why is your question in the past tense?”

We’re still all learning how to do all of this.

BUT there is good news and a good experiment coming from Jakarta.

The government is integrating the angkot into Jak Lingo, TransJakarta’s cashless fare collection system. The system is also changing the business model for the angkot operators, moving them away from fare based income into service contracts.

…angkot operators agreed to integrate their services with Transjakarta, meaning that passengers need to pay only once with an electronic card to enjoy the service. In the scheme, angkot drivers are paid based on the distance they cover, regardless of the number of passengers they carry. The city administration has sought to expand the integration with other modes of transportation, including other minibuses, the MRT and the light rapid transit (LRT)…

ITDP, which helped design and plan the TransJakarta BRT system tells us more:

Jakarta’s microbus drivers were previously paid out of passenger fares only, which encouraged them to only pick up as many passengers as possible, with no incentives for a safe, comfortable, or efficient ride. Buses often left late, waiting to be full of passengers before leaving, and indirect routes to continue packing the bus were common. Today, all of the city’s microbus cooperatives now pay drivers salaries, although they remain independent operators within contract. Transjakarta provides a guaranteed salary to each driver in exchange for following a predetermined route on a set schedule. The salary rate also encourages drivers to drive longer routes that may include fewer passengers, but enable Transjakarta to reach new areas of the city. Drivers can now focus on providing service, safety, and following their routes in a timely fashion. Previously common behaviors like speeding or skipping stops are no longer necessary.

Ini bagus!

(This is great!)

Apart from moving angkot into service contracts, the Jak Lingo integration also provided benefits for the children of the drivers.

The Jakarta administration plans to expand the recipients of the Jakarta Smart Card Plus (KJP Plus) student support program in 2019, with the inclusion of children of Jak Lingko public transportation drivers. The policy…stipulates that KJP Plus recipients are children aged from 6 to 21 years old whose parents are drivers of micro-buses that are partnered with Transjakarta.

Tunggu sebantar

(Wait a minute.)

Since you’re learning all about angkot, you should also learn about omprengan, which is Indonesia’s version of casual carpooling or slugging.

Dwiyanti Kusumaningrum tells us more in this article in The Conversation (via google translate).

In small towns or even in rural areas, omprengan is usually a worn-out car used to pick up traders to the market in the early hours when public transportation is not available in an area at a certain time.

However, in Jakarta, omprengan was adopted as an alternative mode of transportation that supports the mobility of commuters to share vehicles (ridesharing ) on their way back and forth from the office in central Jakarta due to limited public transportation.

Omprengan is technically illegal but is very much tolerated, but for sporadic crackdowns by the government. (Just like all of informal transportation.)

Julia Nebrija, my colleague and Agile City Partners co-founder, likes to point out that this is why cities and metro regions need to embrace and work with informal transportation. The booming cities of the Global South grow so much faster than the government’s ability to plan and deliver public transportation. Meanwhile, people need to get around.

Nyanyikan saya sebuah lagu

(Sing me a song.)

I leave you with this jazzy tune about angkot. Its a parody of the song Akad by Payung Teduh which topped the Indonesian music charts in 2017.

“Akad” means “contract.” The video of the original shows a taxi driver musing about the relationships he sees in the people who ride his cab. The parody by Kerry Astina shows the travails of an angkot (or angkod) driver. It gives you a great feel of the angkot riding experience.

Enjoy!

Sampai bertemu!

(Catch you later!)

Let’s wrap up this letter. Apologies if I got the Bahasa phrases wrong. Do share your experiences if you’ve ever ridden an angkot.

I’m Benjie de la Peña and I’m the CEO of the Shared-Use Mobility Center. I co-founded Agile City Partners, and I am the Chair of the Global Partnership for Informal Transportation.

I’m convinced that informal transportation can be the single greatest lever to decarbonize the urban transport sector, but only if we stop ignoring it and instead learn to celebrate it so we can transform it.

Minangkabau people, also known as Minang, are an ethnic group native to the Minangkabau Highlands of West Sumatra, Indonesia. The Minangkabau's West Sumatran homelands was the seat of the Pagaruyung Kingdom, believed by early historians to have been the cradle of the Malay race, and the location of the Padri War. Wikipedia

Great issue. I rode in a lot of bemos when I lived in Bali for a college semester. Growing up riding the T in Boston didn’t prepare me for the intimacy and improvisation of bemo transit. Boston drivers get a deservedly bad rap, but bemo drivers in Bali were on another level, at least back in the ‘90s.