#15 Real Time Resilience

Why you should consider informal transportation in your climate change plans

Hey there friend,

Thanks for welcoming me into your inbox.

Hope this (*takes deep breath*) fortnightly-newsletter-on-innovations-in-informal-transportation finds you well.

Did you ever have a pen pal?

I think I tried to when I was in my early teens. I only got as far as one or two letters.

I imagine being like Jack Nicholson in About Schmidt writing, “Dear Ndugu…”

So, I have sad news.

You didn’t win the free copy of Kenda Mutongi’s Matatu: A History of Popular Transportation in Nairobi which I offered in my last letter to you.

No one did.

No one put a comment.

(Sad face emoji.)

Not your fault. I forgot to put a clear link to the comments, like this:

No worries. We’ll bounce back up and try again.

Speaking of resilience…

I was in a virtual workshop a couple of weeks ago run by the engineering firm ARUP for the Asian Development Bank. The topic was “The Future of Transportation.”

I couldn’t pass up the invitation because I am totally into scenario planning and futures thinking (I supported groundbreaking work in the past) and because I came to waive the banners of informal transportation.

I was able to get a virtual post-it or two on the virtual workshop board.

There was a lot of talk about resilient transportation because one of the undeniable future trends is climate change. (“What do you mean ‘future’?”)

The engineers and policy analysts in the virtual room were mostly thinking about resilient formal transportation. By that I mean more of:

How would you design and build a climate change resilient light rail system?

Or, climate resilient BRT?

I didn’t hear much of:

How do we make tuktuks and jeepneys climate resilient?

Which was a shame because makeshift mobility is inherently resilient.

All that ingenuity and adaptation come from people and communities bouncing back, creating and recreating new things with whatever is left over and available.

People who run informal transportation and communities who use informal transportation ARE being resilient in the face of oppressive forces, be it benign government neglect or mismanagement, a lack of concern or investment, or unvarnished hostility.

All that innovation is a response to need and context.

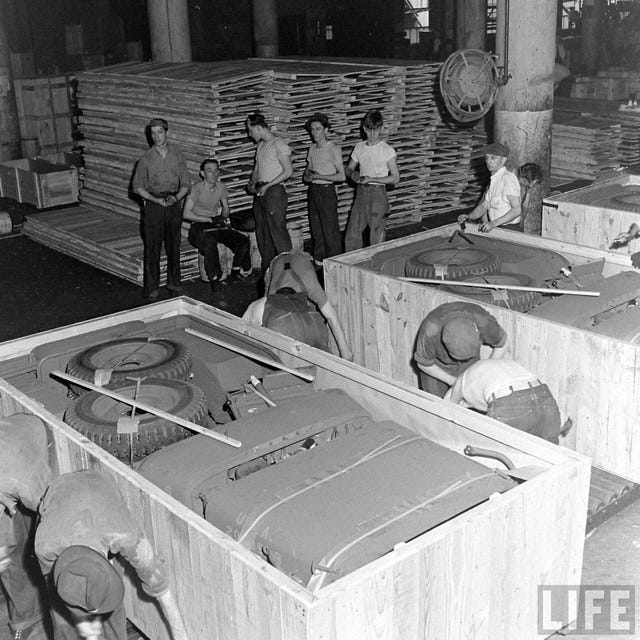

World War II destroy your urban infrastructure?

Well then, look at all those leftover flat-packed military jeeps.

Let’s turn that into public transportation!

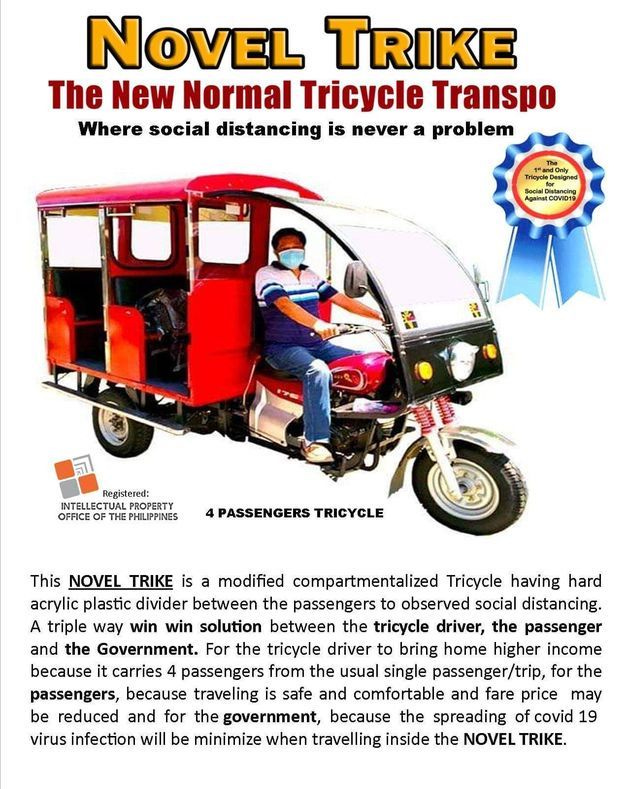

Makeshift mobility has resilience in its DNA an the invention and reinvention continues today.

Constant adaptation

I stumbled into the work of Zach Hyman. Zach is, “a researcher, designer, and author whose interests include service design, strategic design, and studying daily life and behaviors.”

Here he is presenting a pecha kucha on how Chinese informal vendors are adapting three-wheelers into mobile kitchens and the like.

(Btw, one of Zach’s books available for download is a gorgeous treatise called Yangonomics: Reflections on Yangon’s street-level economy.

If you are fascinated by indigenous design, anthropological investigations, and the informal economy, go download it. Better yet, if you can afford it, go buy it .)

Constant change

If cities want to imagine what resilient urban transportation looks like, they have to include makeshift mobility in the mix. They have to account for, even leverage, all that adaptability and ingenuity.

I know, I know.

The resilience experts will say adaptation is not resilience, etc., etc.

But, if we’re honest, it really doesn’t matter what you call it. What is important to the person on the ground is that their needs are met, whichever way it takes.

Makeshift bamboo repair of an overhead bus railing, from Zach Hyman’s Yangonomics

Real time resilience

All of that adaptation happens in real time, in the midst of the struggle, no virtual workshops required.

Resilience on the (small, fast, and) cheap

I don’t have the numbers but I bet it would be cheaper to invest in informal transportation—to upgrade to green vehicles, to change the economic model so it’s not a precarious livelihood, to make vehicles safer—than it would be to build new, climate resilient, formal transportation infrastructure. (Don’t @ me.)

Makeshift mobility would also automatically adapt to sea-level rise.

Peseros, tuktuks, tricikads and ojeks can go where formal systems would fail.

The formal transportation won’t ever have the coverage of informal transportation anyway.

…everywhere

Urban Age at the London School of Economics argues for the essential role of informal transportation in COVID-19 recovery.

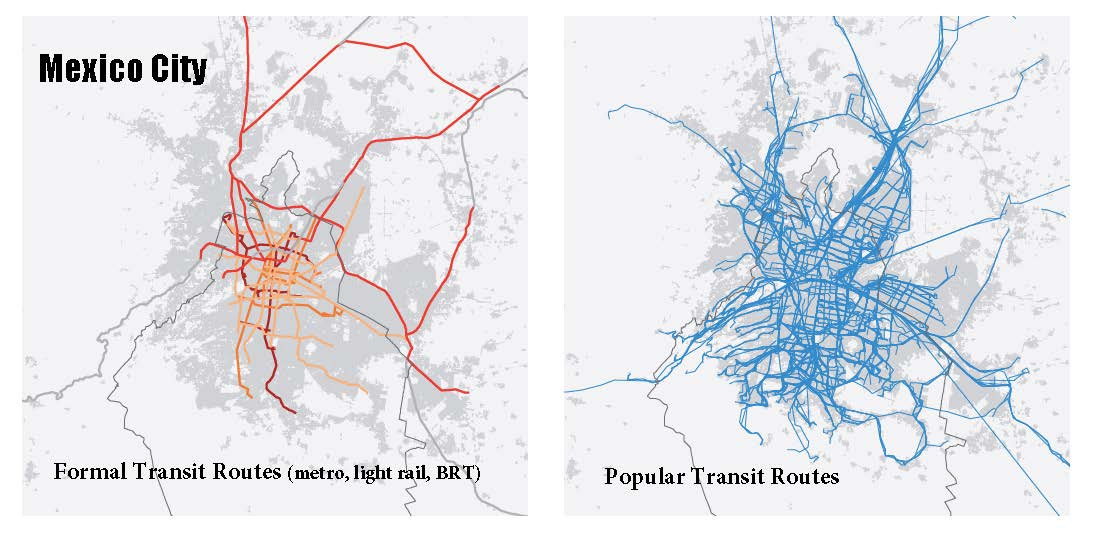

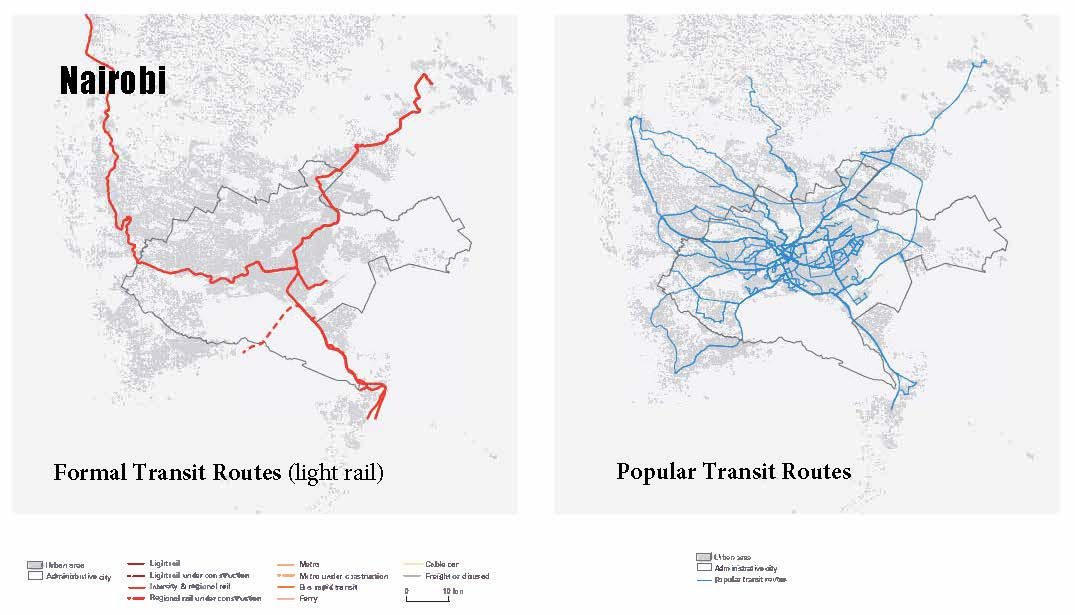

They showed the comparative coverage of formal transportation vs. informal transportation in Mexico City and Nairobi.

As the maps above demonstrate, formal mass transit routes (red) only cover a relatively limited urban area, whereas informal routes (blue) reach far more people and are often the only access to motorised transport for low-income urban dwellers. Small, privately operated minibuses are one of the most important informal modes: In Nairobi, 70% of commuters rely on privately run ‘matatus’ to get to work, while 74% of all public transport trips in Mexico City are completed on ‘colectivos.’ In addition to the vital role these services play in getting people to work, informal transit is itself an important employer. In Kenya, the informal transport sector and associated services are estimated to employ nearly half a million people.

LSE calls it “popular transportation.”

I guess to mean “for the people,” but does it imply that formal transportation is NOT popular or not for the people?

I’ll go with “makeshift mobility.” Thanks.

Cashless = less cash?

Speaking of not popular, remember when we talked about cashless fare collection?

Yes, it’s an awkward segue. Sorry.

I told you that we need to draft design principles to make sure nothing falls through the cracks. We really need those principles, otherwise we run into problems like Tap&Go users in Kigali complaining that their stored value fare cards are “eating their money.”

Phiona K (other name withheld on request) is a business consultant that frequently uses public transport buses to move around Kigali while meeting her clients.

She purchased a Tap&Go card and loads money that can take her through a month.

“I once topped up Rwf7500 onto the card and traveled only once from Kanombe to the city centre and back,” Phiona told Taarifa on Monday, adding, “after one month, I went to board the bus but when I tapped on the bus gadget, it indicated that there was no money of (sic) the card. I was embarrassed.”

…According to commuters interviewed by Taarifa in the past one year, they complain that they top-up for weekly rides but the money lasts only 3-4 days.

That’s the problem with stored value cards. There is no easy way for the user to know how much value is left in the card. It’s not only inconvenient for the commuter, it’s also a real temptation for the fare collection system operator.

The aggregate amounts can be yuuuge.

At any one time in the U.S., the total value of unused gift cards are at least $20 billion. Yes, billion.

The U.S. had to make it illegal for stored value gift cards to expire in less than 5 years precisely because some unscrupulous stores and companies were selling cards that would “expire” in months or weeks.

Guess who gets to keep the money?

Palate cleansers

I don’t want to leave you this week on that unsettling note, so here’s a palate cleanser:

I am keeping an eye on the work of Halan in Egypt. CNN had a great short feature on Mounir Nahkla, one of the founders.

It’s really inspiring when the tech solutions for makeshift mobility come from seeking empowerment for the under served, rather than from value capture. (Of course, I could be naive and it could all be PR.)

Also, I’m a panelist next week at a UITP webinar on “Key Factors of Success to Formalise Informal Transport and the Significance of Authorities.” (tl;dr -we haven’t actually seen “success.”)

I think registration is free. Go sign up.

Alright folks, that’s all the news in Lake Wobegone.

(That’s an NPR reference. It’s OK if you don’t get it.)

I’m Benjie de la Peña, a transport geek and urban nerd. I live in Seattle, currently the city with the second worst air quality in the world. Thanks, climate change.

I think a lot about strategic design, institutional shifts, and innovation.

I believe makeshift mobility could be the single greatest lever to decarbonize the urban transport sector—but only if we can organize. (And I am organizing!)

If I had my druthers, the world would have an international, inter-city think tank dedicated to improving informal transportation.

When I think of transport resilience, makeshift transportation is my first thought! flexible routing that can respond to emergencies or changes immediately, as they feel market demand most acutely. (I also wrote a little bit about this after some travels a few years back: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/resilience-transport-nerd-travels-southeast-asia-madeline-zhu/). Would love to hear your thoughts on how improvements/digitalization of information flow between passengers and operators (demand/supply) could bolster that resilience further!

Zach's shawarma vendor example is perfect. "The power of these vehicles [is to] get around the failings of urban planning." Makeshift transportation may be the fastest way to create mixed-use development where it didn't exist before.