Hey Friend,

Just a week late with this fortnightly dose of innovations and what-nots in informal transportation. I hope you don’t mind.

Maybe I should drop the “fortnightly” and go with “occasional” -?

Speaking of time, the 2nd Mobilise Informal Transportation Global Meet & Greet is just nine days away. Have you registered?

Let’s downshift from our discussions about decolonizing transportation and talk about the excellent Chicken Buses of Central America.

Like their cousins, the matatus of Kenya, the jeepneys of the Philippines, and the colectivos of Argentina, the chicken buses (a.k.a. colectivo, caminioneta) of Central America are proudly, garishly decorated. They are mobile pieces of pop art that celebrate local culture.

Just search for “chicken buses Central America” on Flickr and ogle those beauties. You’ll find more lovely pics on travel blogs like this one.

Did you notice the yellow buses in those Flickr streams?

Chicken buses are refurbished (I would say upcycled) school buses from the U.S. There’s a booming market in used school buses and a supply chain that drives (pun not intended) the retired buses from US auction houses to Central America.

The buses are gutted. Their drivetrains replaced with newer, more powerful engines. Then they are ornamented and personalized before they serve as public transport.

I touched on that conversion process in Makeshift Mobility Issue #32 and shared Mark Kendall’s documentary on how a used school bus becomes a colectivo, caminioneta, or a chicken bus.

If you don’t have 2.5 minutes to watch the trailer for Kendall’s film, I’ve got you.

Here’s a 1.5-minute explainer from AJ+.

There’s a whole other life for used school buses, not just in Central America.

The danfos of Nigeria are yellow because they adapted the yellow of the bigger molue buses. Molue buses were, you guessed it, imported used school buses.

That’s all part of this massive supply chain of used vehicles from the Global North that gets exported to the Global South, where they are repurposed and serve informal transportation.

That’s why I’m worried about the World Resources Institute’s (WRI) Electric School Bus Initiative. The Bezos-funded initiative is pushing to electrify all school buses in the US by the end of the decade. That’s a fleet of over 450,000 yellow buses.

Electrified school buses are great, but where will all those fossil-fuel-burning buses go? To the Global South, of course.

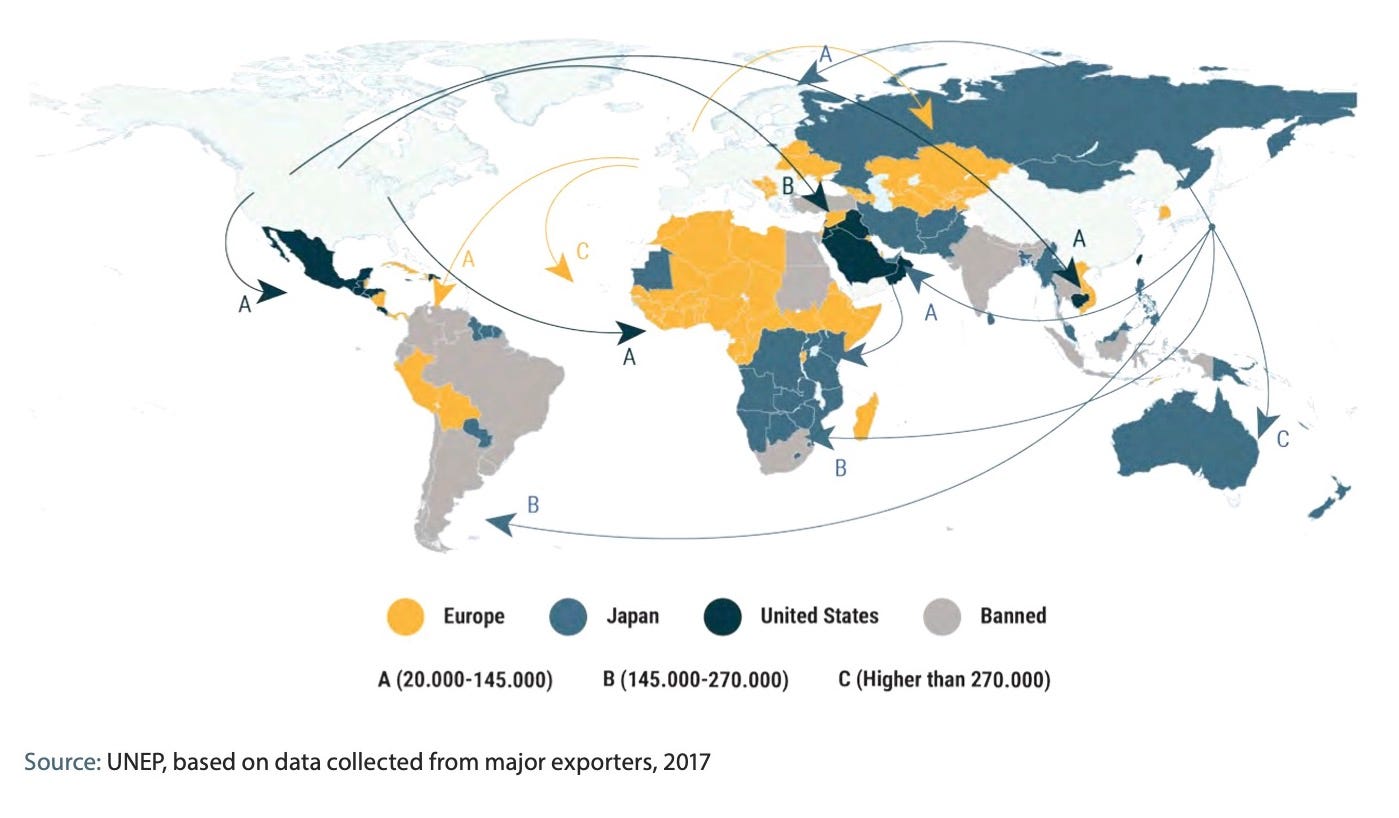

UNEP’s Used Vehicles and the Environment - A Global Overview of Used Light-Duty Vehicles: Flow, Scale and Regulation gives a global snapshot of this material flow.

Millions of used cars, vans and minibuses exported from Europe, the United States and Japan to the developing world are of poor quality, contributing significantly to air pollution and hindering efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change, according to a new report by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP).

The report shows that between 2015 and 2018, 14 million used light-duty vehicles were exported worldwide. Some 80 percent went to low- and middle-income countries, with more than half going to Africa.

So, while the Global North reduces their carbon emissions by selling more electric vehicles and replacing their gas and diesel guzzlers, those vehicles and the carbon they emit just get sold to the Global South.

Every year, the United States ships hundreds of thousands of its oldest and dirtiest cars overseas to predominantly poor countries in a trade that is largely unregulated. In other words, cars that would fail safety, fuel economy and emissions standards in the United States or Europe are dominating the roads in countries that rely on imported vehicles.

“The pollution and gas guzzling continue on even after the vehicle is removed from America’s roads,” said Dan Becker, head of the safe climate transport campaign at the Center for Biological Diversity. “It’s essentially a Cheshire cat issue.”

Beyond exporting the carbon emissions, a surge in the supply of used vehicles will destabilize the markets in the Global South.

My friends in WRI tell me that they are very conscious of the afterlife of the used school buses. It would be great if WRI could include that concern in their initiative.

WRI’s list their initiative’s goals (“focus areas”) as:

Aggregate demand to drive mass procurement of electric buses

Scale e-bus manufacturing and drive down unit costs.

Develop innovative utility and private sector financing models and support smart charging infrastructure deployment.

Unlock public funding and policy support for full electrification of school bus fleets.

Galvanize communities and stakeholders for an equitable and comprehensive shift towards e-buses by 2030.

May I suggest that they add:

Upgrade the export supply chain to electrify the used school buses when they enter (and are upcycled) in the markets of the Global South

What’s that?

“But Benjie, those countries don’t have electric charging infrastructure? Even if we could electrify them, how would you charge all those buses without a grid of EV chargers? The batteries will also make it cost-prohibitive.”

I worried about that, too, until I read about this battery swapping service for trucks in Australia.

Developed by Janus Electric, the batteries can be swapped in three minutes, removing the need for trucks to plug in and charge for up to 12 hours…

“By doing the conversion on existing trucks, and it’s not as difficult as everyone thinks because everything is manufactured to a standard. So there’s commonality between the trucks….”

Typically, conversions take around a week, and will be carried out on trucks that are already due for an engine rebuild, which often comes around every five years.

“It’s usually the diesel engine that’s worn out, not the rest of the truck,” he said, “so, instead of spending money on the rebuild, they can convert their trucks.”

Could we equip the Global South chain that upcycles old buses and mini buses from the US, Europe, and Japan with swappable battery technologies and electric drivetrains?

The current upcycling process already happens through a network of small-scale companies and workshops. The homegrown mechanics and artisans already have the know-how. They already practice grassroots innovation when they turn those school buses into rolling works of art. We could equip those mechanics and artisans with the tools and parts that they need to clean up makeshift mobility.

I think we could. What do you think?

(Someone forking out another $100M might help.)

IMHO, without the added focus, electrifying school buses in the US and sending them down the export chain to the Global South is another incarnation of colonialism in transportation. (Oh, no. We’re back there again.)

Ok, all for now. I leave you with these tidbits:

CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology Co Ltd), the Chinese company that dominates the electric car battery market, just launched a battery swap service called EVOGO, which “would allow drivers to change car batteries in one minute.”

Gogoro says Taiwan will soon have more battery swapping stations than gas stations.

I’m Benjie de la Peña. I’m the CEO of the Shared-Use Mobility Center. I co-founded Agile City Partners, and I am the Chair of the Global Partnership for Informal Transportation.

I’m convinced that informal transportation can be the single most significant lever to decarbonize the urban transport sector, but only if we stop ignoring it and instead learn to celebrate it.

Since my first time in Africa, I witnessed that public transport mechanics can MacGyver any vehicle and make it run if they have to. Heck, you'll see drivers by the side of the road, scanning the immediate area for anything that might be improvised into a tool or a replacement part – and then they will perform a miracle before your eyes. With the right incentives, Africa's fleet of second-hand buses would be retrofitted to electric power in no time.

I wonder how much it would cost. The West to buy its old gas guzzlers back if it neglects its power grid enough, or turns away from the Natural Batteries God has given us in the form of coal an oil and natural gas long enough to be so dependent on the "Renewables" that can only be counted on for at best 25% of the time and cannot get started in the morning because the batteries are dead and there's not enough juice running through the wires?

The Third World could get rich off the stupidity of Westerners who have killed the giants on whose shoulders they have placidly surveyed the world.