Hey there,

Here’s the 21st issue of Makeshift Mobility, your fortnightly newsletter on innovations in informal transportation.

We’re in the final month of 2020. I’m tempted to do a retrospective but maybe we’ll save that for the 24th (one year) issue. Best to get 2020 behind us.

Btw, have you found your place in the COVID vaccine line? NYT’s little estimator tool tells me that I’m behind 268.7 million other people in the U.S.

That’s fine. I’m neither essential nor am I at high risk. Meantime, I’ll keep my mask on.

This newsletter is essential for transportation geeks. Please share.

Does your home country or the country you reside in have a prioritization list?

Healthcare workers come first, anywhere in the world. Then essential workers.

People who work in public transportation are considered essential workers in the US. I think the same goes for the EU.

Where are the informal transportation workers on the COVID vaccine line? Does your home country or the country you reside in consider them essential?

Let me know with a comment.

I had some very interesting conversations over these past two weeks.

On the Edge with Roland

I had a great time talking to Roland Harwood.

Roland produces On The Edge, a podcast “all about making unexpected connections, everywhere and anywhere. It features conversations with people who are living and working on the boundaries of organisations and places, and seizing new opportunities, and avoiding the pitfalls, of our increasingly connected world.”

What was supposed to be a meet-and-greet phonecall turned into a great conversation. Or, maybe I just talked Roland’s ear off.

He recorded the call then quickly turned it into the 24th episode of the podcast.

Thanks to Roland’s amazing editing, the podcast succintly captures the key ideas of why informal transportation is important.

Roland (and On the Edge) is part of Liminal, a “new, global network of creative, strategic, technical and entrepreneurial people from wildly different backgrounds.” Gina Lucarelli who leads UNDP’s Accelerator Labs connected us. (Thanks, Gina!)

(I’m absolutely flattered to be listed among Roland’s interviewees. He’s featured Cassie Robinson, Tessy Briton, Rutger Bregman and many other people who inspire me. )

I also had three other conversations with people taking tech to informal transportation. I learned a lot.

An app for informal transportation in NYC

I also had meet-and-greet calls with Su Sanni and Jordan Magid from Dollaride.

Dollaride is the first app serving the NYC Dollar Van Market, the Big Apple’s homegrown informal transportation system.

About 120,000 people take dollar vans in New York City every day, about double the number from two decades ago, according to industry estimates. There are roughly 2,000 drivers, three-quarters of them operating illegally.

I frequently mention NYC’s dollar vans in my presentations to show how informal transportation emerges in cities in the Global North, even cities with very established and extensive formal transportation services.

Su and Jordan told me of the bureaucratic hurdles that dollar van operators need to go through to become “legal.” They include paperwork that takes as much as three months to process, about $5,400 in fees, and insurance requirements that can cost up to $1,200 a month. No wonder most operate illegally.

Dollaride wants to change all that, eventually. For now they are using a B2B model to get companies and business improvement districts (BIDs) to create routes that serve their customers and employees in transit deserts.

(Su also founded WeDidIt, an online fundraising platform.)

A white label mapping service for informal transportation

I met with Marc Hasselwander who runs data analytics for Trufi Association. (I had to reschedule so missed meeting Christoph Hanser, one of the founders.)

Trufi is a mapping solution for informal transportation in the mold of Digital Matatus. Started and initially staffed by Open Street Map volunteers, Trufi offers their app and platform to cities and civic associations as an open source, white label service.

Trufi’s first deployment was in Cochabamba but are pursuing contracts in other cities in LatAm, in Africa, and in Asia.

A system manager and a new business model

I’ve also been having great conversations with Philip Cheang, Kenneth Yu, and Wilhansen Li—the co-founders of Sakay.PH

The Philippine’s Department of Transportation is rolling out Service Contracting for all buses and jeepneys across the country. Sakay.PH won the contract to be the System Manager for the project.

Phil, Ken, and Wil have been picking my brains on what to think about as they roll out the system. (Full disclosure, Sakay.PH provided an honorarium, for which I am grateful.)

I’ve been pushing for Service Contracting since the start of the COVID lockdowns. It would keep transportation running and to save the livelihoods of the drivers and operators.

I am intensely interested in the success of the project as it would be breaking ground by addressing informal transportation simultaneously on two fronts:

Changing the business model of informal transportation, and

Using real time tracking to manage the system.

Service contracting would have government pay the drivers and operators to run the services, which potentially divorces the service from the passengers=income dynamic that drives system and driver behavior.

Real-time tracking will make the system visible not just to government but also to passengers and, perhaps more importantly, to the drivers and operators.

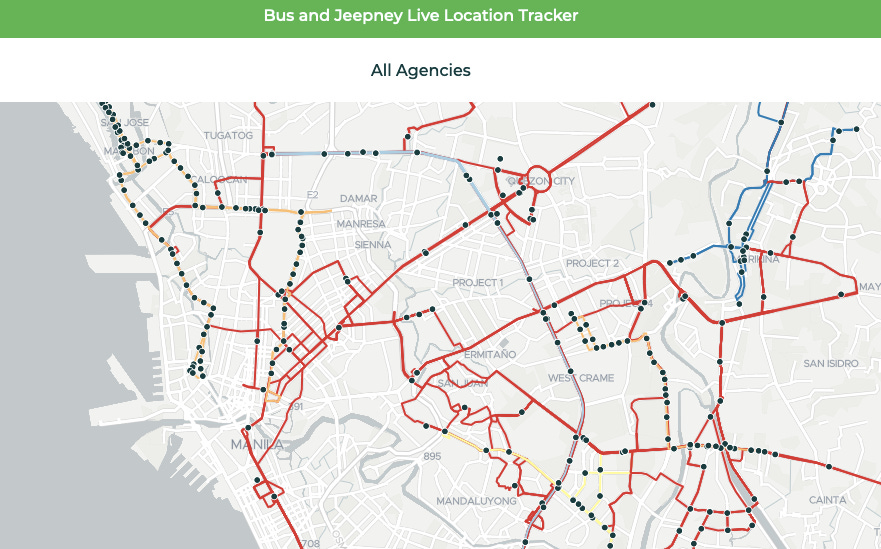

Sakay’s real-time tracker is live. They are working with the Land Transportation and Franchising Regulatory Board (LTFRB), the agency tasked with rolling out service contracting, to work out the kinks in the system.

Disruption and despair

One more thing.

I hope you caught Amanda Sperber’s excellent piece on the devastation left by Uber’s disruption in Kenya. Amanda tells us the story via the experience of Harrison Munala. Harrison started driving for Uber four years ago. The going was good in the first year that Harrison took on a car loan. But things have definitely gone south.

Four years later…Uber slashed its fares — and Munala's income. It also introduced new categories of cars, allowing smaller cars. And more people started to take the smaller cars because they were cheaper and more fuel-efficient.

That adversely affected the drivers who were already saddled with the larger, four-door cars with more powerful engines that Uber had previously required.

More and more drivers flooded the platform, changing the basic earning premise that had prompted people like Munala to take out loans to become drivers.

And car maintenance is costly. Fuel prices are high. Instead of owning an asset, Munala is saddled with growing debt.

He fell behind on his rent. He, his wife and their three children were evicted from their home in August. They are sheltering in a church while he tries to raise money to build a house.

Harrison is not alone.

Uber employs more than 12,000 drivers in Kenya. All of the more than 80 people who were interviewed expressed distress and said they were barely making ends meet.

I mention this here because informal transportation and shared-use carry so many similarities, not the least of which is the emerging vehicle-rent model that’s at the base of makeshift mobility systems across the world.

The vast majority of the Uber drivers interviewed in Kenya said they do not own their cars and instead drive "partners'" cars — renting them from other people.

My main worry is, without a clear understanding of how we want to transform informal transportation with technology, we will simply be digitizing (and supersizing) the oppressive systems that rule these critical services.

Something to think about.

That’s it for now. Catch you in two weeks.

I’m Benjie de la Peña and I wear many hats. I co-founded Agile City Partners, and I am the Chair of the Global Partnership for Informal Transportation. I will be wearing other hats, soon. Hats that work in cold weather.

I believe makeshift mobility could be the single greatest lever to decarbonize the urban transport sector. My cats don’t understand but they cheer me on