Hey there,

I’m hitting your inbox a bit late this week. It was my birthday! (Yay, me!)

In lieu of gifts, just share this email with someone you think would appreciate it. (I’ll certainly appreciate it.)

If you just signed up, welcome!

Makeshift Mobility is all about innovations in informal transportation. I land in your inbox every fortnight. Feel free to leave a comment or say Hello.

Auto correct

Francisco Uribe at Ford called me out. I had been spelling “collectivo” with two Ls.

It’s “colectivo.”

One L.

Thanks, Francisco.

I blame auto correct.

Ok, maybe that’s a weak excuse but it does remind me of how aggressive, even offensive, auto correct is.

Automated oppression

Madeline Zhu of Swiftly left a comment in Issue #15 about resilience.

She shared a piece she wrote about how informal transportation in Cambodia shows “the power of a decentralised, flexible system that could respond to hyper-local conditions in real time.” She said it’s the kind of resilience that could be enhanced and enabled by mobility algorithms.

I agreed with Madeline but I said it would depend on how we deploy the algorithms. I compared auto correct on phones and tablets vs. background spelling and grammar check on writing apps.

Auto correct’s algorithm is so aggressive. Aggressive!

It gets in my way and changes the word right before I press enter to send a message. I often have to go back and retype a word.

It is particularly insensitive to bilingual and multilingual users. (Really, it’s algorithmic microaggression.)

Grammar and spelling assistants ever so gently just put a squiggly red underline on words it thinks I misspelled or on sentences with bad grammar. Right clicking brings up suggestions but it leaves it up to me to make the correction.

Of course, the algorithms originate from the same technology. (It was invented by Dean Hachamovitch at Microsoft. WIRED has the fasinatng…fascinating history.)

The difference is in the implementation.

As we develop algorithms to manage informal transportation systems (and I believe we will), I prefer they operate more like background spell checkers vs. auto correct. More gentle nudges of expertise than heavy handed authority.

Which brings me to what I want to highlight this week: the clumsy, heavy hand of governments who try to bring order to informal transportation systems.

Can you imagine what aggressive algorithms could do in the heavy hands of governments intent on “order.”

Order on demand

Late last year, Egypt’s government moved to ban tuktuks from Cairo and other cities.

In September (2019), Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly announced a sweeping plan to phase out tuk-tuks in 20 governorates, swapping them for seven-seater gas-powered minivans. The proposal, offering drivers a payoff period of up to five years, bars all tuk-tuks from cities and main roads but allows new and licensed tuk-tuks to continue operating in narrow alleys and rural villages.

Egypt wants to replace the tuktuks with vans—but the operators have to pay for the new vans. (Which possibly look like this.)

But skeptics question the logic of changing a tuk-tuk prized for its tiny size, high maneuverability and cheap fare for a microbus that manufacturers expect to be four times the size and price.

It’s not the first time Egypt is trying to regulate away the tuktuk.

But the “tuk-tuks have ruled the streets of Cairo’s slums for the past two decades, squeezing through dusty alleys, dodging trash bins and fruit stands, blaring rhythmic electro-pop and navigating the city’s chaos to haul millions of Egyptians home every day.”

So, don’t expect it to be easy.

“People will be trying to resist, to circumvent these developments, to go on living,” said Yasser Elsheshtawy, professor of architecture at Columbia University. “This is something very Egyptian.”

Apparently, also very Kenyan.

Banning the bus

Nakuru, the country’s third largest city, recently banned matatus from the central business district. A decision that did not go well with the minibus operators.

They lit bonfires and barricaded roads within the CBD as they demanded audience with the governor.

They accused (Nakuru County Governor) Mr Kinyanjui of dumping them in new matatu terminuses which are in poor state without shades and basic amenities like toilets and water.

Nairobi is trying to do the same thing, banning the matatus from the CBD. Predictably, it is facing the same level of resistance.

The operators resist and it never goes well for government because makeshift’s mobility’s roots are in self-help and in making-do under constrained resources.

Makeshift mobility is used to resisting.

Ingenuity and insurgency

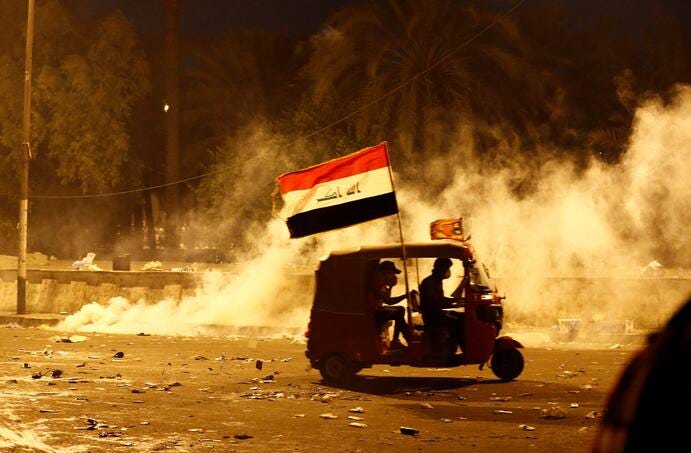

Did you know that Iraq’s uprising in 2019 was called “the tuktuk revolution?”

A tuk-tuk speeds away from tear gas fired by Iraqi security forces. (Thaier Al-Sudani/Reuters) via WaPo.

A Washington Post report, from November 2019, said:

More than 200 Iraqis have died and thousands more have been injured in the anti-government protests over the past month, which have been fueled by poverty, rampant corruption, unemployment and crumbling public services. Iraq’s once-marginalized tuk-tuk drivers — symbolic of how hard life had become for average Iraqis — have been front and center, keeping the movement, literally, alive…

Tuk-tuks came to Iraq just in the past few years as a response to rising congestion and as a cheaper alternative to taxis. The motorized rickshaws had been largely used just in Sadr City, one of Baghdad’s biggest and poorest neighborhoods. Tuk-tuks can easily navigate the area’s narrow and unpaved roads.

Same themes.

Makeshift mobility serves the poor and the experience of that struggle becomes really useful when the time comes to resist.

What’s absent in the reporting in Egypt and Kenya, is also absent in nearly every report about how governments deal with makeshift mobility: the impact on the people who use informal transportation.

AP reports tuktuks are “especially popular with disabled people, the elderly and women who want to avoid harassment at crowded bus stops.”

Makeshift mobility is popular with the excluded and oppressed.

You can’t extract informal transportation from the informal city, what Robert Neurwith calls System D or l'economie de la débrouillardise —the economy of resourcefulness.

Using ingenuity to survive the daily struggles of having less also means a willingness to struggle to against impositions of that will make life harder.

Innovation and all that new stuff

“But Benjie, you said this was about innovation. Everything you wrote about is from a year ago.”

Ok, ok.

If belated news about insurgency is not your thing, here’s some interesting bits. Let’s start with three whelers in the U.S.:

Chicago is extending a pilot tuktuk service. Aldermen have called the service, run by a firm called Tuk Tuk Chicago (how appropriate), as a “responsible small bus operator.” The pilot is running in the city center but aldermen are interested it letting it run in neighborhoods.

Jacksonville FL’s transit authority announced a partnership with a local firm to provide tuktuk service to the CBD and two neighborhoods.

Image from tuktuk-chicago.com

Meanwhile, in the quest to provide cleaner fuels for informal transportation, sodium could one up lithium batteries.

A team from the Deakin University’s Institute of Frontier Materials in Melbourne won a global green business ideas competition “for developing sodium batteries to electrify motor scooters, buses and auto-rickshaws in Indonesia with the goal of cutting carbon dioxide emissions.”

The team–PhD student Karolina Biernacka and early career researchers Dr Faezeh Makhlooghi Azad, Dr Jenny Sun and Dr Vahide Ghanooni Ahmadabadi–said their project “aims to compete with current battery technologies which can be unsafe and rely on dwindling and expensive global reserves of lithium and cobalt.”

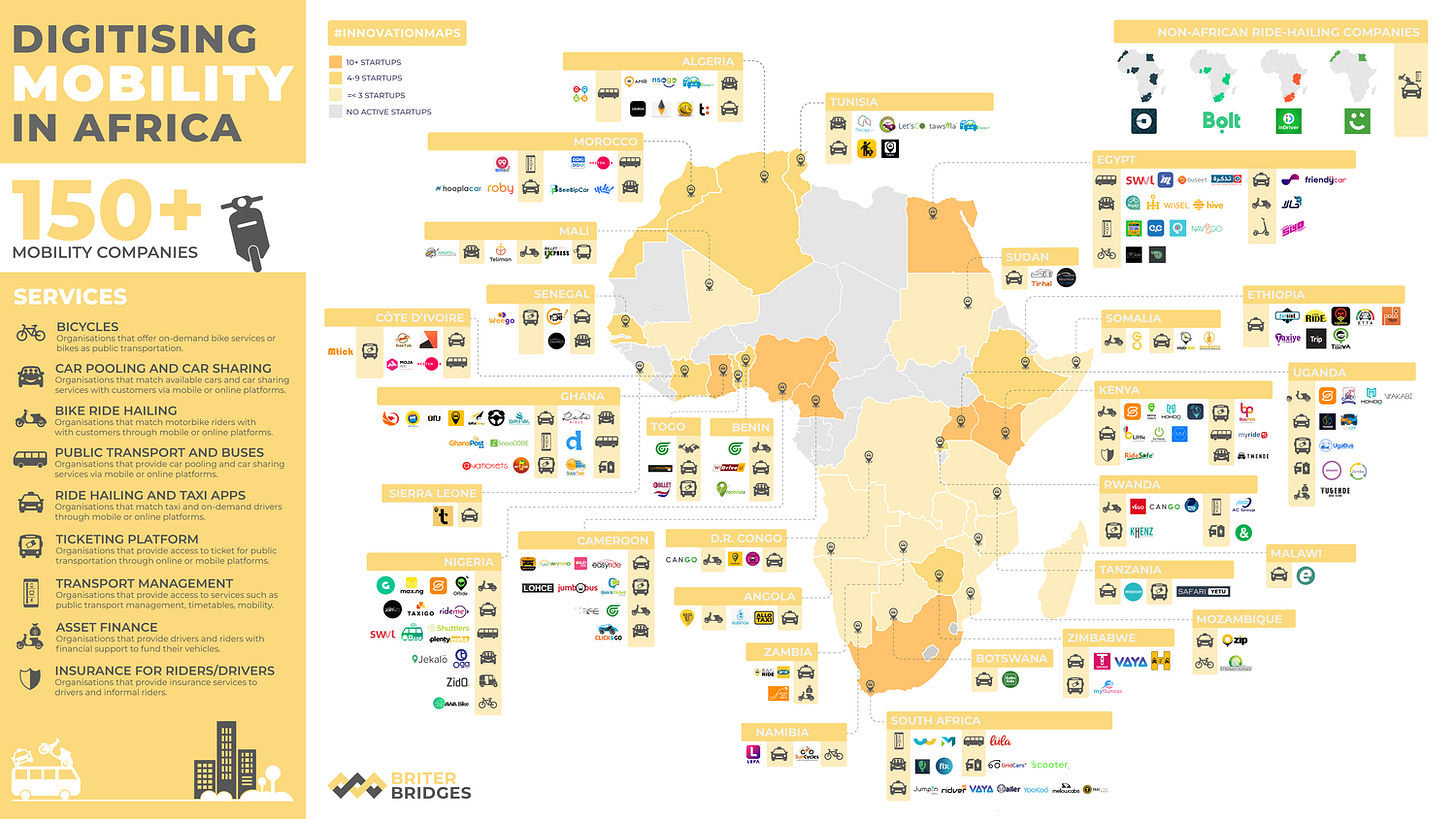

From Thet Hein Tun at World Resources Institute, a tip that led me to these gorgeous graphs from Briter Bridges mapping innovation in Africa.

My favorite, of course, was this one on mobility:

Pretty coolbeans if you asked me.

Ok, last question before I leave you. What’s the right way to spell it?

“tuktuk”

“tuk tuk”

“tuk-tuk”

“auto rickshaw”

Leave your answers in the comments.

That’s it for this week. See you in two.

Stay safe. Wear a mask.

I’m Benjie de la Peña, a transport geek and urban nerd. I live in Seattle. I’m cooking something up, something global, something about informal transportation (of course). I’m really excited.

I believe makeshift mobility could be the single greatest lever to decarbonize the urban transport sector—but only if we can organize. (And I am organizing!)

Re your point that makeshift mobility users are often marginalized, I think a lot of bans happen because the decisionmakers don't consult these users/ are far removed from the second and third order impacts of their decisions. Two personal examples -

1. Singapore government's e-scooter or PMD ban from last year - While I know e-scooters are much maligned and do have many safety concerns, these devices were the only source of income for 1000s of food delivery riders in S'pore and proposed alternatives (bicycles, e-bikes, motorbikes) just didn't work for a variety of reasons. (Disclosure - I worked at a micromobility operator co and our local biz was affected)

2. The Supreme Court of India's ban on diesel buses in Delhi from a few years ago - great from an air quality standpoint, especially considering Delhi's current pollution levels, but a decision that made it close to impossible for millions to get to work. And since I grew up in Delhi, it's auto rickshaws for me always :)

Love your newsletter!

A lot of these bans are closely tied in to some connected politician with a specific vehicle or engine import franchise. When we were doing the cycle rickshaw modernizatino project in India we had a hard time getting our lighter and more comfortable designs adopted because the big player in the industry controlled the rexine (? - some sort of plastic used for the seats) import monopoly. So we changed the seat to use rexine and then they were good with it.